FROM OUR AUGUST ISSUE: PLASTICS AND OUR PLANET

The entire MR team is proud to present our August 2023 issue. Haven’t gotten your copy, yet? Feel free to page through a digital copy at Issuu, and we’ll continue to post individual stories on MR-mag.com. If you haven’t been getting MR in print, be sure that you are on our mailing list for future issues by completing this form.

During the Covid lockdowns, I read a number of surveys concluding that few consumers identify polyester, nylon, or elastane [spandex] as plastics. With most of our clothes now made from plastics (more than 65 percent and growing), I felt the knowledge gap needed correcting.

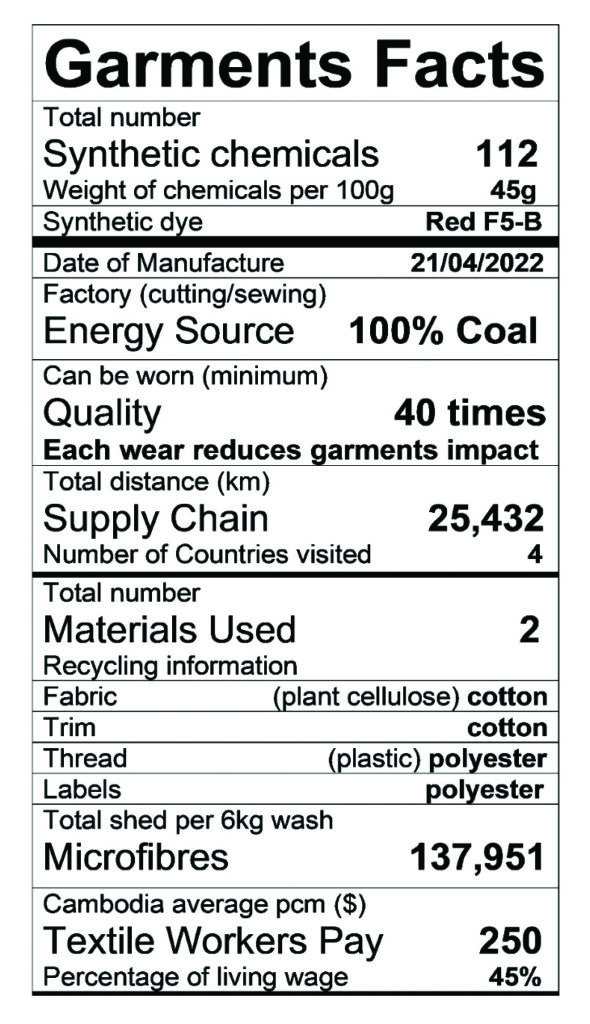

Looking at current regulations, apparel makers need only provide information about the composition of the main fabric and country of origin. Is that enough? I believe there needs to be a list of all the materials used, including threads, trims, buttons, zips, labels, and even dyes. Providing this additional information would be advantageous for recycling the garment in the future since new technology can recycle both fabrics and dyes.

I set about describing a garment via its data from a selected number of metrics. (There’s inherent flexibility, depending upon which metrics you have data for.) Choosing a T-shirt as an example, I used my network of experts to provide data about chemicals used, supply chains, energy sources for manufacturing, etc.

To effectively communicate this information, I needed a “vehicle” and selected the nutritional label that’s been used for decades by the food industry. Consumers are familiar with this format and can readily digest the information.)

To highlight some of the chosen metrics: Date of manufacture is key. It can act as a tracking metric from first purchaser to end of life. Would you purchase a second-hand automobile without knowing its age? Also important is a description of materials used, stating polyester as a “plastic” and cotton as “plant cellulose.” The total supply chain distance (km) and number of countries visited helps to provide a more complete picture than just “country of origin.”

A social metric is usually missing, or only voluntary, from current and future proposed legislation. The Garment Facts Label provides details of textile worker pay from stated manufacturing facilities, comparing these to minimum wage and living wage calculations. In a commercial environment, verification of self-reported data (including pay and location of production facilities) is essential. There are mechanisms to validate data but also costs associated with such validation.

Future regulations, particularly in Europe, aim to stamp out vague sustainability claims (known as “greenwashing”) made by fashion brands. In the future, brands will need to provide real data to substantiate such claims. Europe is also proposing a Product Environmental Footprint (PEF) to inform consumers about the impact of consumer products, including textiles. This is based on Life Cycle Assessments (LCA), where impacts are calculated for 16 categories.

This past spring semester, seniors at the Fashion Institute of Technology used this garment facts label for their final research project (thanks to Professor Sal Giardina); many are now challenging mills and manufacturers to do the same. Imagine a time when consumers will have all the information needed to make wise purchasing decisions to help save our planet.

Peter Gorse is a textile researcher at Cranfield University, UK. For more information, email: p.gorse@cranfield.ac.uk.