RACISM IN MENSWEAR

A menswear exec from one of America’s top specialty stores recently asked MR to investigate the troubling topic of racism in our industry. A few months back, when the murder of George Floyd and Black Lives Matter protests began flooding the news broadcasts, a woman came into his store, asking to see product from Black designers or Black-owned companies. Perusing his selling floor, this merchant was embarrassed to acknowledge that in his vast menswear mix, there was just one Black designer. Just one!

The subject of racism in our industry is clearly too layered and complex to do it justice in a short feature, especially one written by a white writer who has not personally suffered the repeated humiliations brought on by racism. (These include, but are in no way limited to: being followed by security guards in upscale stores; sales associates checking with managers before accepting your credit card; being stuck for years in assistant positions while less talented white colleagues get promoted; walking down an aisle on a plane as white women in their seats instinctively clutch their handbags; a warm introductory phone call changing to an icy in-person reception; being called the n-word; witnessing a major department store reject ads with black models; and on and on…)

In an attempt to begin a conversation that we hope MR readers will continue, we ask a few industry people of color to share their personal experiences with racism, and their suggestions for moving a bit closer to the diversity and social justice our industry, and our country, so desperately deserve.

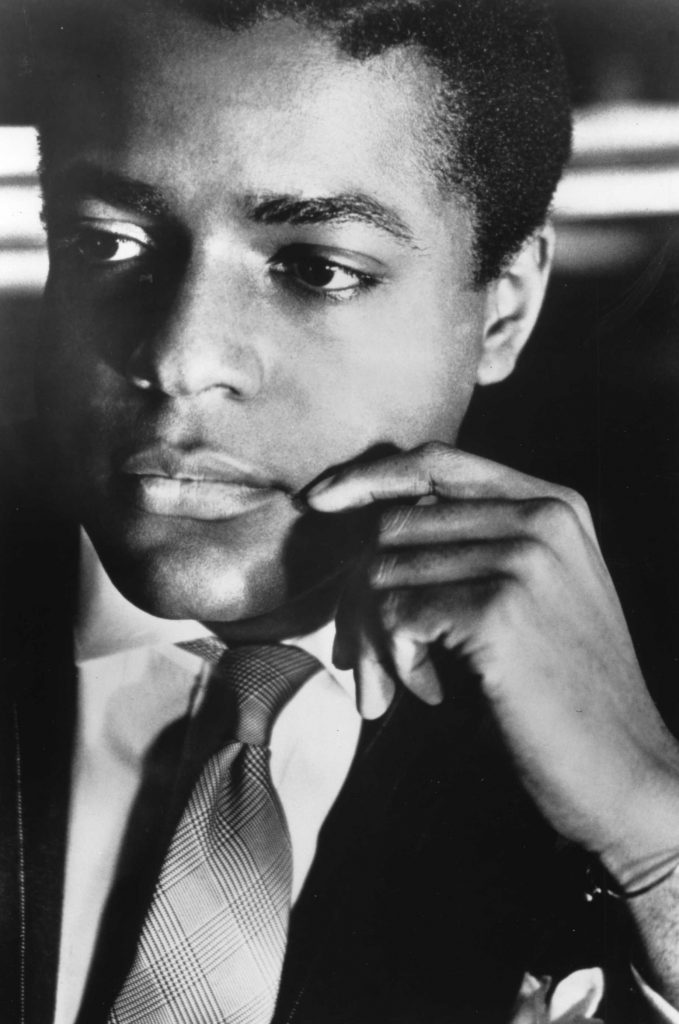

JEFFREY BANKS, DESIGNER AND AUTHOR

One race-related experience that’s stayed with me dates back to when I was 17. I’d just started working for Ralph Lauren who took a chance on me right out of high school. (We’d met when I was selling clothes at Britches of Georgetown in Washington, D.C.; I loved Ralph’s designs and sold a lot of them. We’d have great conversations about the history of men’s style.)

At the time (August 1971), Ralph was just launching women’s fashion and wanted to get in with Stuart Kreisler, a women’s fashion mogul at 550 Seventh Avenue. So, Ralph sent me to 550 to check it out. It was a hot humid summer day and I was wearing black linen pants, Gucci loafers, Halston sunglasses, an open-collar shirt, and a sportcoat. The elevator operator took one look at me and told me I’d have to use the freight elevator. I watched as other guys wearing open collar shirts got on the regular elevator and I realized for the first time that I was targeted because of my skin color.

Why are there are so few designers of color in our industry? For one thing, it’s so difficult for Black designers to get financing. When I started out, applications for bank loans were coded with a C (for Colored).

But it’s not always racism. I meet many young Black designers who are talented artists but don’t know the business side. Backers are looking for commercially salable product, not art. The buyer at Saks Fifth Avenue doesn’t care about race or gender, only whether or not the stuff will sell. In a precarious economy, banks are nervous about backing unknowns of any color. And who’s out there to teach these talented young people how to run a business, how to do a 5- to 10-year plan?

I’m particularly proud of the CFDA Incubator program that gives emerging designers free showroom/atelier space for a year. Smart landlords recognize that this will bring income-bearing tenants down the road; we need more people looking toward the future.

And retailers need to step up to the plate: instead of knocking off name designers, why not give young people a chance to shine. To attain diversity, the fashion industry first needs to be cognizant of the imbalance. Why aren’t more people like Bill Gates getting involved to help diverse communities own businesses? A good business model is Shinola in Detroit: with a depressed car industry, they figured out what else could be made in America and hired people from the community who needed jobs, training them to be self-sufficient.

Retailers also need to revamp training programs. In the early ‘70s, executive training, although hard work for little pay, was a strong foundation for a retail career. Trainees were exposed to all aspects of the job, from curating product in buying offices to dealing with customers on selling floors. Today, trainees spend all day in a cubicle looking at spreadsheets. We’ve got lots of talented young people not being properly trained.

We’re all entrenched in a system of institutionalized racism and the only way to change it is to talk about it. I don’t have the ultimate solution but I’m willing to talk about it and I’m optimistic that things will actually change. Just look at the diversity of protesters these past few months—across the country and around the world. Young, old, Black, Asian, Latino; in some cities, the protestors were mostly white! I believe people are really sick of the injustice and that we’re finally turning the tide. It’s no longer us vs. them; it’s all us.

SHARIFA MURDOCK, CO-OWNER OF LIBERTY FAIRS

Among the worst things I’ve endured as a Black woman in a corporate position: a company I once worked for hired an inexperienced person over me and expected me to train that person! This was done with no explanation, and when I questioned it, they called me a disgruntled employee. As the first Black woman to own a trade show (Sam Ben-Avraham gave me that opportunity at Project years ago), I’m extremely proud of the diversity we continue to build here at Liberty.

But for most Black women in business, climbing the corporate ladder is draining —always trying to avoid judgment, which is why I wanted to become an entrepreneur. One example: I’ve been wearing my hair in braids since the pandemic, something I’d never do in a corporate situation since it’s perceived as ghetto. Black women have to work extremely hard to avoid being stereotyped.

Unfortunately, prejudice is built into most corporate structures. There’s always an excuse so top executives don’t have to acknowledge it. It’s been going on so long that some don’t even realize they’re pre-judging. I’m hopeful that all the recent conversation surrounding social justice, police reform, and Black Lives Matter will finally make a difference. Now that people are working from home and watching more news, they’re paying more attention.

My fundamental hope is that people will no longer have a reason to be afraid. And at the end of the day, it’s up to us to lead the charge, to hold people accountable. I’m part of Black in Fashion Council, an organization advocating universal commitment to diversity so that all fashion companies ultimately become 15 percent Black. We’ve always had that commitment at Liberty: diversity is intrinsic to who we are. We don’t go out looking for Black designers but it happens organically because 1.) We’re always seeking new talent, and 2.) Black designers feel more comfortable in places where minorities are better represented.

Most important: Black employees are not asking for handouts or special treatment; we’re just asking for equal treatment. May we continue to move in that direction.

GARY WILLIAMS, OWNER OF GARY WILLIAMS SHOWROOM

Our industry is no better or no worse than others. Like most African Americans in our country, I’ve experienced my share of racism: both overt actions and those little micro-aggressions that affect us nonetheless.

At my first wholesale management position in the fashion industry, I was hired to head men’s sales. I worked really hard and was successful forming relationships with some great stores: Fred Segal, Murray’s Toggery, The Rogue, Shaia’s, Barneys New York. It was going so well until the day that I was suddenly demoted: I was told that certain southern retailers might be ‘uncomfortable’ working with me, that they’d prefer a ‘good ole boy’… It was the late ‘80s and there were very few people of color in the business; I had no Black mentors to advise me. It was a bitter pill and I was devastated but I had to accept it: the underlying message was that I should be grateful just to have a job there.

After that, there were the typical humiliations: I’d be setting up my booth at MAGIC and people would assume I was a workman, not a sales manager. Or I’d make a showroom appointment over the phone and upon meeting face-to-face, the buyer would be shocked and clearly uncomfortable to be working with a Black man. Among people of color, we call it a ‘seen-us’ problem… This happens so often in business that we become extremely adept at reading the cues and putting people at ease. In a sense, we have to become the adult in the relationship. (And as it’s been said: the best revenge is to sell them!)

I’ve always been an optimist in my core: I believe in people, I believe in America. And I believe that this moment that we’re in will be a turning point. They say you have to hit bottom to create change; if this isn’t bottom, I don’t know what is. If people aren’t feeling something so visceral in their souls as they watch videos of George Floyd being murdered or of the multi-cultural, multi-generational protests, they’re not human. I think most people know what’s right; it’s just that some are fearful, having spent their whole lives in a capsule without ever having a genuine relationship with a person of color.

So, I remain optimistic, now more than ever. We’re finally having the kind of uncomfortable conversations that need to be had among people who value each other. Companies are suddenly calling me, asking for my advice on how they can promote diversity. My generation tiptoed around it; young people are charging though it. And I believe young people will make it happen.

What should fashion companies be doing? Go where the talent is: SCAD, FIT, Parsons, RISD, Berkeley College, LIM. We’re not talking affirmative action hires: these are truly talented young people who will make your company stronger if given the opportunity. So, I say find them, hire them, empower them, or at least give them an internship. I’ve had 40-50 interns over the years and many have gone on to do fantastic things. Now is the time!

LIZETTE CHIN, PRESIDENT OF MEN’S AT INFORMA MARKETS

After 400 years of oppression, I totally support Black Lives Matter. Racial inequality and social injustice are problems that have always existed and need to be dealt with.

Although I’m a woman of color, I identify more as Latina than Black and experienced minimal racism growing up in a multi-cultural neighborhood in Queens. I do remember as a young girl an incident of graffiti on our screen door. But I think it was more about my parents looking interracial (my dad dark-skinned, my mom fair) than it was anti-Black.

In my career, I believe I’ve had more challenges as a woman than as a person of color. I’ve always tried to overcompensate, never allowing myself to assume that any setbacks were about race. I’ve always prided myself on being color-blind and that’s how I raised my kids. But in retrospect, I wish I’d paid more attention to race: noticing it, respecting it, honoring it, learning from it, asking questions rather than pretending we’re all on a level playing field. Because we’re not.

At Informa, we’ve started conversations with our Black executives and we’ve established a committee to affect change: Informa Markets Fashion for Change. We believe that small changes can have big impact. We believe in spotlighting Black talent via incubator programs, and in hiring more diverse creative talent. Our ambition is to work with educational institutions that have a large minority enrollment to provide talented students a gateway to the fashion industry.

But, bottom line, the best way to affect change in our industry is to educate and collaborate, to have those uncomfortable conversations, to listen and respond.

EDWINA KULEGO, VICE PRESIDENT OF LIBERTY FAIRS

The biggest issue Black employees face is the uneven playing field and the fact that systemic racism is not more widely acknowledged. I don’t think people who are not Black can understand what we go through every single day.

As for upward mobility, Black employees are told to be grateful for where we are, as we watch peers with lesser skills get praised and promoted. I’ve seen very talented Black employees stay in assistant positions for years. In my exit interview at a company I worked for, I pointed out that they have many brilliant, talented, motivated Black employees who haven’t been promoted in ages.

Fortunately, people are more vocal now, more willing to call out companies for racial profiling. They’re demanding accountability: in hiring practices, in decision-making. How companies handle this will affect their brand image and their revenue.

It’s ironic: Fashion is such a diverse industry and Black culture is such an important part of it. How can brands reflect diversity if no one is flagging racial stereotypes if the decision-makers all look the same if their advertising reflects insensitivity? H&M, Balenciaga, Gucci, Prada, all have made racially offensive marketing faux-pas lately. If there’d been a Black person on their executive team, this would not have happened. Why is no one paying attention?

EDWARD ARMAH, DESIGNER

Of course, there’s racism in our industry but it’s so pervasive that many are blind to it. Like others from my country (Ghana), I came to the U.S. to work, having no idea how tough it would be. I started my men’s accessory business 11 years ago and suddenly found myself dealing with all-white mills, all-white banks, all-white retailers. While I’ve made many wonderful friends in our industry over the years, I’ve also put up with much hurtful treatment and I often question why I stayed. But I don’t want to give up: I can’t disappoint my kids.

I’m not sure I care to recall all the humiliations I’ve experienced over the years, but here are a few. A buyer from the south who I thought was my friend (we haven’t spoken in years) once said to me, “Edward, you’re different. You’re the only black person I can call my (n-word)…”

A store owner in the south once told me, after I traveled across the country to personally present my collection, “Your neckwear is beautiful but I’ve never bought anything from a Black man and I’m not starting today!” A different southern retailer asked me if I work with Minister Farrakhan.

I was once driving in the Midwest with a bunch of menswear reps on our way to a trunk show. I’d taken the first morning flight from Newark airport and, totally exhausted, fell asleep in the car. So, we’re driving from the airport to the store and I’m sleeping in the car and they drive me to a corn plantation. They thought that was funny…

For anything to change, white people have to be willing to listen. Some try, but how can they really feel our pain? I’m in more than 100 better specialty stores yet maybe 10 percent have me listed on their websites. You wonder why I’m the only Black designer at many trade shows? How many Black designers can afford $200,000 to build a business? The economic disparity between races is based on lack of opportunity, not lack of talent. There’s so much that needs to be fixed.

Will our industry really open a diversity platform? Will companies seek out Black talent? Will we develop a training structure with mentors? We’ve tolerated so much for so long and still, I wonder: what kind of legacy will I leave for my children?

A few suggestions: Let’s aim for more inclusion in our tradeshows, showrooms, buying offices, manufacturing, and media. Let’s select from an expanded talent pool for a more diversified industry. Let’s embrace change and make sure all parts of our industry reflect that change. Let’s keep the American dream a beacon of hope for all.

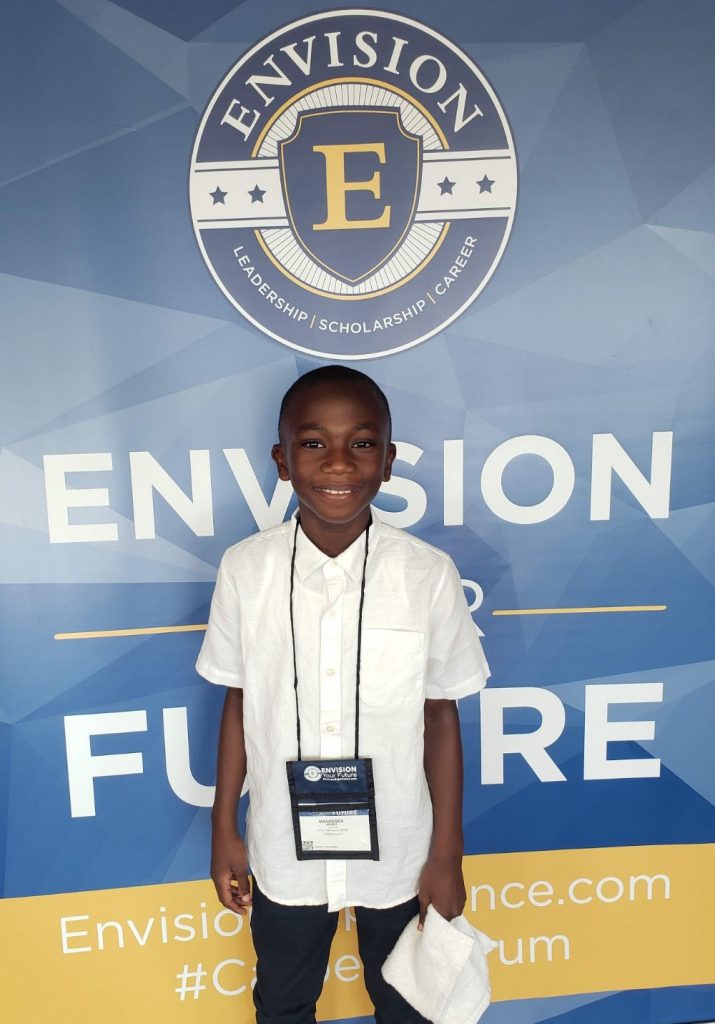

Fight for What’s Right

By Manasseh Armah, age 10

When I sit and think, is life really fair?

I sit in my chair and stare in mid-air.

With thoughts that hurt to say out loud,

Racism is a dark and scary cloud.

It always happens out of notice,

But people around us have been witness.

Lies and words to make us feel better;

Black people should back down no longer.

Stand up for yourself and make a change,

It’s never too late to rearrange.

This has been my poem about racism:

Fight for what’s right; every voice matters.

I own a retail boutique and I would like to include diversity training when on-boarding new staff. I am having trouble finding a good training program. Most of the reviews I’ve read about the current programs are that they “miss the mark” when talking about diversity. I was wondering if anyone has any info on a good programs I could reference?

Hi AJ, I don’t know her personally but check out http://www.RishaGrant.com—she’s a well respected diversity and inclusion expert!

Good luck and thanks for reading MR!

I really love my cousin for writing this article. You are so right to highlight what has been happening for generations under our noses. Seeing what is happening and calling it out is one step to making change happen.

AJ,

http://www.derrickgay.com

I’ve heard nothing but good feedback from those who attended his training.

G.

There is a very good on in FIT.

Thank you Karen, Jeffrey, Sharifa, Gary, Lizette, Edwina, Edward, and especially Manasseh.

Jim Bresnahan

Wow! Truly astounding, Thank you Jeffrey, Sharifa, Gary, Lizette, Edwina, Edward and Manasseh for sharing your stories. It takes a lot of strength to be subjected to these horrifying situations and remain as passionate as you obviously are about this industry. We are listening, trying hard to learn from your experiences and make changes where we are able. Thank you

Heidi

Thankyou for a great article. Important topic that we all need to address. Responsibility with our organizations.

Thank you Karen, Jeffrey, Sharifa, Gary, Lizette, Edwina, Edward and Manasseh for sharing your stories and your nightmares. As some have mentioned, it’s an uncomfortable conversation but now couldn’t be a better time to say “enough is enough”!

I remember a conversation we overheard during an MR show a number of years back that amplified the ugliness existing in our industry. The n word was used towards a waitstaff in the dining area. Recently, I was stunned by a Facebook post by a Facebook friend who’s post was “liked” by some additional industry colleagues and their crew. Not only was it about people of color but demeaning in gender too!

Not to sound industry like but what has been sewn into the fabric of this nation, can be torn up and recycled into a new realm of possibilities. That starts from one’s soul and to disavow the group think amongst “The Good Ole’ Boys”.